Original Source

Thousands are left furious, terrified after PPO plans dropped

By Jenny Deam

December 5, 2015 Updated: December 8, 2015 12:49pm

More than 88,000 people in the Houston area have lost plans from Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas for 2016, potentially cutting off some of the most seriously ill from the top-tier medical care the city has built its reputation on.

Last summer, the state’s largest insurance carrier dropped all preferred provider organization plans from both the Affordable Care Act’s federal exchange in Houston and the private individual market.

Now, with only weeks to go before existing plans expire, patients, doctors and hospitals are scrambling to find what care is available under the insurer’s replacement health maintenance organization plans.

“Jody would be dead if she didn’t have her oncologist,” said Steve Schoger of his wife, his voice catching. The Woodlands couple had their plans canceled.

Both have cancer; both are in experimental clinical trials at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center they fear cannot be replicated elsewhere.

They are at turns furious and terrified.

Even if the former PPO plan holders shift to one of BCBS’s HMO plans on the exchange, those with the most complex medical needs still could be forced out of certain types of specialty care and left to find similar lifesaving treatments elsewhere.

PPOs typically offer more latitude in choosing treatment, while less-expensive HMO networks are more restrictive.

M.D. Anderson, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston Methodist and Memorial Hermann – all at the Texas Medical Center – will be out-of-network in BCBS’s HMO exchange offerings for 2016, according to the insurance company. Those with employer-sponsored group plans are not affected.

Dr. Robert Morrow, president of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas’ Houston and Southeast Texas Region, said in a recent interview that the decision to drop 367,000 PPO plans across Texas, even though customers were paying more for them, was driven by economics. He called the plans “unsustainable” after his company lost $400 million by paying out more in claims than it collected in premiums.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas is a division of Health Care Service Corp., which operates in Texas, Illinois, Montana, Oklahoma and New Mexico.

‘The right decision’

“It was a very difficult decision, but it was the right decision,” Morrow said.

M.D. Anderson, ranked first in cancer care in the nation last summer by U.S. News & World Report, is not covered by a single major insurer on the exchange.

Nationally renowned Houston Methodist and Texas Children’s Hospital also are mostly shut out of the federal marketplace by major insurer HMO plans.

Houston Methodist is in-network in Cigna plans only. Patients wanting treatment at Texas Children’s must navigate a maze by signing up for Community Health Choice’s HMO and then selecting Kelsey-Seybold Clinic as their primary provider, hospital officials said. From there, a Kelsey-Seybold physician will determine if a referral to Texas Children’s is warranted.

Hundreds of doctors affiliated with Houston’s marquee hospitals are also now out of network in many 2016 individual HMO plans, hospital officials said. That includes 250 pediatricians who are part of Texas Children’s Pediatrics group.

“You have some of the world’s best medicine in the Texas Medical Center, where people come from all over the world, yet here is this segment of the population in Houston. People who live here can’t access it,” said a clearly frustrated Mick Cantu, an executive vice president at Houston Methodist. “You can stand there, looking up at the building right in front of you, but you can’t get in.”

While acknowledging that most people with routine medical needs will find good doctors and hospitals in the narrower networks, he discards what seems to be the insurance industry’s belief that all care is interchangeable.

He said he finds the changes drastic and puzzling. Many of the patients affected are middle-class, used to having broad coverage and willing to dig deep into their pockets because they do not qualify for a tax subsidy on the exchange or have bought off the exchange entirely.

MORE INFORMATION

United Healthcare mulls full ACA exit

Last month, the nation’s largest insurer, United Healthcare, announced it was considering pulling out of the ACA’s federal and state exchanges entirely in 2017. Company officials projected losses at $425 million for this year, saying its half-million customers were sicker than anticipated and used more health services.

“It’s one thing to say there is a narrowing of networks. It’s another thing to say you can either have a narrow network or nothing,” Cantu said.

‘We’re being punished’

At least 2,700 patients at Methodist have been affected by the loss of PPO plans.

Dianne Duncan is one of them.

“We’re being punished for picking physicians who are the best at what they do,” she said, moving slowly across her Richmond living room, wincing in pain when she thinks no one is looking.

Duncan, 64, and her husband, Mark, 66, are self-employed communications consultants. They bought their PPO plan in late 2013 during the first ACA open-enrollment period, not because they were sick but in case the worst were to happen. Six months later, it did.

In the summer of 2014, within two weeks, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer and she with advanced-stage colorectal cancer. Growing up the daughter of a doctor, she had always been told: “If you have something serious, you go to the Medical Center.”

A flurry of calls led both to highly respected doctors, oncologists and surgeons. Duncan had his surgery at Memorial Hermann in September 2014. His wife had hers two months later at Houston Methodist. Both have been cancer-free for a year butneed follow-up care. Duncan now qualifies for Medicare, but his wife does not.

Neither her doctors nor her hospital will be in-network under the HMO plan their insurer offered them.

“I feel deserted,” she said last week as she waited for the results of a colonoscopy to make sure her cancer has not returned. “What if they find something?”

Her husband feels something closer to rage.

“I think the object in all of this is to go back to the way it used to be, so (insurance companies) can pick and choose who they want to cover,” he said.

Similar concerns

Dan Fontaine, executive vice president of administration at M.D. Anderson, has similar concerns about the disappearance of exchange coverage for Houston’s prestige medical institutions: “Why so fast? Why so complete?”

“The management of risk used to be handled through denials of pre-existing conditions,” he said of pre-ACA days. “It is now being handled through the narrowing of the marketplace.”

Certainly the pre-ACA reality of only getting the widest coverage through group plans is returning, he said.

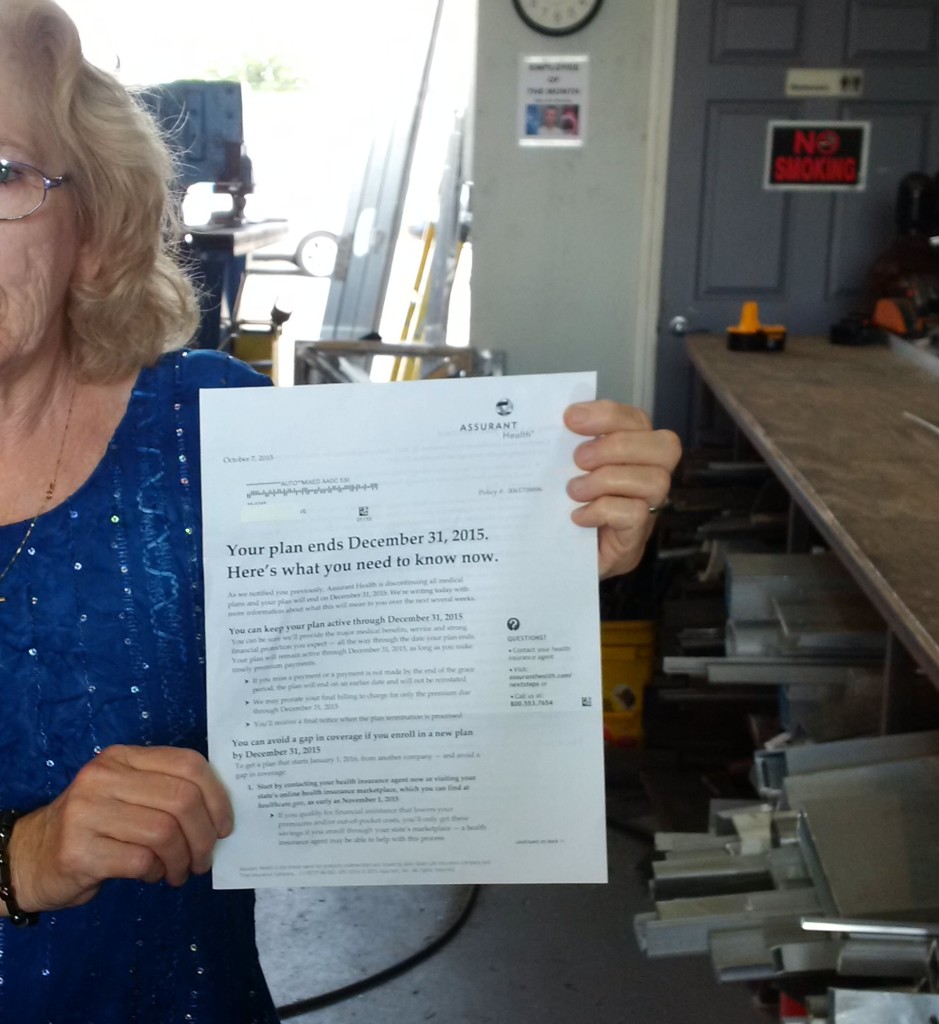

Last year, 19 PPO plans were offered in the Houston region. When the 2016 federal exchange and private market opened on Nov. 1, there was none. Eliminated plans expire Dec. 31, and enrollees, looking for replacement plans, have been urged to find one by Dec. 15 to ensure uninterrupted coverage.

Cigna offered seven PPO options on the Houston exchange last year but now also has none. A spokeswoman said in an email that no one from the company would be available to discuss the reasons.

It also would not disclose the number of customers in the area affected by the loss of its PPO plans.

Morrow, at Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas, explained that by law his company sets rates based on all individual members’ claims history, or a single risk pool. If the payouts in one plan are high, it raises the prices of all plans. Since most people buying on the exchange have chosen lower price over broader choice, insurers have jettisoned the more expensive plans – and presumably expensive providers.

Costs harder to control

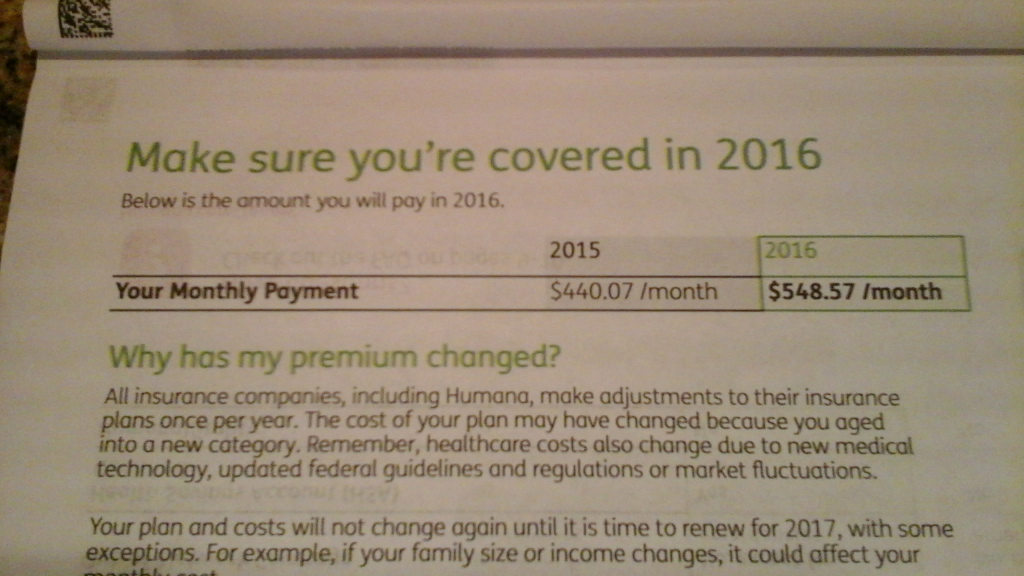

PPO plans typically cost insurers about 20 percent more than HMO plans because they are less able to control costs in where customers seek treatment. A study by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation last month found that nationally, two-thirds of insurance companies offering PPO plans for 2015 either reduced the number of plans or dropped them completely for 2016.

Morrow said his company does offer one HMO plan that allows some out-of-network choice but conceded it came with a “significant” out-of-pocket price tag.

He rejects the idea that his sickest customers are losing lifesaving care at premier medical institutions.

“This is Houston, Texas. There is very good care in the community,” he said, adding that his company would guide any customer in the midst of complex care to an in-network provider.

Not on his life, Jay Solomon countered, meaning it quite literally.

The Houston psychologist, 63, sat in a corner chair in the beige treatment room at M.D. Anderson, with his left arm outstretched as a tube pumped Carfilzomib, an anti-cancer drug, into his vein. He was diagnosed in 2009 with incurable multiple myeloma, a cancer of the plasma cells that produces tumors in the bones.

In 2012, his condition worsened, and he found treatment at M.D. Anderson, a decision he believes prolonged his life. He now goes for chemotherapy every two weeks, as his doctor continues to try new treatments.

For two years, Solomon had a bronze Blue Cross and Blue Shield PPO plan. He paid $618 a month in 2015 and quickly reached his $6,000 in-network deductible.

To stay at M.D. Anderson and continue with his doctor, he will have to pay out-of-network costs on an HMO plan that could mount to at least $70,000 each year.

For two weeks, he called BCBS customer service, trying to find the right person to look at his case and grant him in-network status since he is in the middle of treatment. Last week, he got the answer: Denied.

He was offered an alternate doctor within the insurer’s network. He has appealed.

“You might be offering me care, but you’re not offering me comparable care. There’s no way I’m not coming here,” he said, his defiance tinged with bitterness.

Countless hours of searching unearthed a little-known option of a small, off-network PPO through Memorial Hermann. Customers must use the hospital’s facilities and doctors or pay out-of-network rates. Solomon said he was willing to pay those rates to stay at M.D. Anderson. He figured between premiums and the $15,000 out-of-pocket cap, he will pay roughly $24,000 a year.

He realizes, though, that he still could be on the hook for any difference between the “allowed amount” for specific treatments and what is billed. That could drive his costs up substantially.

Medical discrimination?

“I thought the ACA was trying to get rid of some of this kind of discrimination,” he said, blaming not the health care law but the insurers he thinks have found a way around it.

Political opponents of what’s known popularly as Obamacare say this is what they warned about all along. Others accuse hospitals and drug companies of price gouging.

A new change.org online petition now with more than 900 signatures takes M.D. Anderson to task, demanding it take patients who have lost individual coverage.

M.D. Anderson officials call the anger misplaced.

“The petition would suggest we at M.D. Anderson refused to accept individual insurance policies and refused to negotiate with insurance companies to be part of their provider network. Neither of those are true,” Fontaine at M.D. Anderson said, adding there is a “consistent pattern” by insurers to offer reimbursement rates much lower than hospital and doctor costs.

Blue Cross and Blue Shield also focused on the hospitals, complaining they will not lower their rates.

“We are willing to talk to providers to get them in our network,” Morrow said. “They made what I can only assume was a business decision to decline.”

M.D. Anderson, Texas Children’s Hospital and Houston Methodist executives all have said they will work with those in active treatment to help them keep continuity of care, although it is not yet clear how.

Randy Steward, director of managed care at Texas Children’s Hospital, insisted his institution “would take care of Texas children.” He also pointed to a Texas Department of Insurance provision that said if a specific service is not covered in-network, the patient would be eligible for coverage by an out-of-network provider.

‘The Scarlet C’

Stuck in the middle are patients.

“I ride my bicycle 6,000 miles a year. I can run circles around the 20- and 30-year-olds. But I got cancer. I’ve got the Scarlet ‘C.’ The PPO says I’m too damn expensive,” said Steve Schoger, a 63-year-old self-employed financial planner.

Jody Schoger, 61, was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1998. The disease went into remission but came roaring back in 2012 and spread to her lymph nodes, abdomen and stomach.

Steve Schoger was diagnosed with melanoma in 2003. Before his diagnosis, he found an individual PPO policy with Blue Cross and Blue Shield, but his wife, because of her pre-existing cancer, was declined. She eventually found coverage through the now-defunct state high-risk pool.

When the ACA became law, she was able to get an individual PPO plan and clung to it. This year, she paid $916 per month; her husband $941.

His wife walked into the room looking stricken. She had just hung up the phone after pleading for an exception from BCBS so she could continue treatment at M.D. Anderson. It was denied. She was told she could use another oncologist in-network. Her husband shut his eyes tightly and forced a smile.

One day later, he also was denied.

“We’ll find a way,” he told his wife of 40 years. “We have to. Our lives depend on it.”